Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Korean Shamanism

http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/Article.aspx?aid=2994354

http://english.visitkorea.or.kr/enu/AK/AK_EN_1_4_8_3.jsp

http://omtimes.com/2013/01/korean-shamanism/

Shamanism is the oldest religious impulse of the Korean people before any foreign born religious/spiritual ideology, such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, came to Korea. Even though its origin is shrouded in mystery it is believed to be linked to a Siberian prototype and to Ural-Altaic civilization. Shamanic practice survived throughout the five-thousand-year-old history of Korea and formed the conscious and the subconscious strata of the Korean psyche.

http://www.gwangjunewsgic.com/online/korean-sayings-a-novice-shaman-kills-a-man/

This is a strange article that has nothing to do with the title-I only include it for some Korean vocabulary.

http://people.duke.edu/~myhan/kaf0911.pdf

Korean Shaman Art PDF

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/06/29/uk-korea-shamans-idUSLNE85S00M20120629

http://www.redicecreations.com/article.php?id=9791

Sunday, December 14, 2014

Saturday, December 13, 2014

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

Monday, December 8, 2014

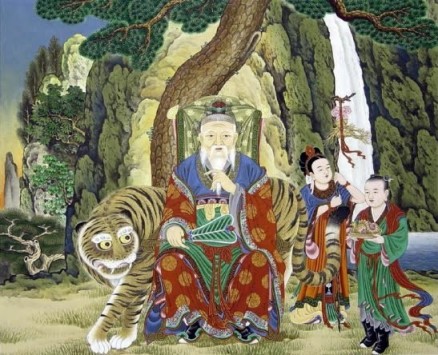

San-Shin

I am having my students write a paper about Korean Shamanism. Today, we were talking about San-Shin, mountain Gods.

Kim Nam Hee said that if a mountain is burning, it weeps."When a mountain is burning furiously, it is wailing."

Lee Hyo Jin discussed the significance of the tiger. She said that after 300 years, the tiger can speak and smoke a pipe. The pipe is called "kom bang dae." In the pipe, he smokes the dried leaves of "yeon jo." I asked what says. Hyo Jin said, "I'm 300 years old. I can speak and smoke a pipe. Cheers!" In Korean society, that is really funny. Below are some pics of Sanshin with tiger, and Korean pipes.

http://cksdigital.manoa.hawaii.edu/photo/items/show/10

http://somewhereindhamma.wordpress.com/2011/02/03/why-did-the-rabbit-give-the-tiger-a-pipe/

"The Tiger is an Angel" Thomas

"He is holding a stick, cha yeon, or pa cho seon, which can change the weather. He is 10000 years old and practices everyday to care for his soul." Tom

The Tiger represents the Korean map (Kristen), which looks like a crouching tiger. (Moon Seri said Dokdo is one of the tigers turds.)

"The tiger represents bravery. The Pine Tree represents the defeat of evil." Coco

The Pine Tree is always blue, which means the correct spirit." HwangSuJin

Sanshin controls the mountain's biology. The tiger protects the San shin. Park Seo In

There seems to be an element of shapeshifting in this. The Sanshin has a tiger spirit, and can shapeshift into a tiger.

http://sacredsites.com/asia/korea/sanshin.html

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Sun Salutation

Mantras to be said with each posture and English translation.

1- Om Mitrayanamah - Oh Sun, You are a friend of every one, let us all be friendly with every one like you.

2 - Om Ravayenamah - Oh Sun, You have bubbling energy, you have sustainable energy throughout the day, let us also have the same sustainable and untiring energy through out the day.

3 - Om Suryayanamah - Oh Sun, You possess only clean and positive energy inside. No pollution you cause while producing energy. Let us also possess only clean and positive energy inside.

4 - Om Bhanavenamah - Oh Sun, You shine with your own energy. Let us all shine in life with our own efforts and achievements. Let us try to be independent.

5 - Om Khagayanamah - Oh Sun, You don’t have any darkness inside, only illumination. Let us also not have any darkness inside. Let us not have any ignorance, let us have only wisdom.

6 - Om Pooshnenamah - Oh Sun, You have enormous energy and you give such a warmth for all beings, let us share only warmth to all those around us.

7 - Om Hiranyagarbhayanamah - Oh Sun, You have a gold fusion energy in the stomach. Let us also have the same fusion energy inside, consume less and produce more, eat less and convert whatever we eat into energy. Let us consume less and leave resources for the coming generations.

8 - Om Mareechayenamah - Oh Sun, You have created such a good atmosphere on the planet where all of us can live in peace and harmony, let us also create a good atmosphere around us so that every one around us can live happily.

9 - Om Adityayanamah - Oh Sun, You are the initiator, you awaken the people every day in the morning. Let us also be the initiators, let us leave our lethargy, our laziness, our boredom and let us be in the fore front of every activity in our life.

10 - Om Savitrenamah - Oh Sun, You have such generosity that you don’t keep any thing back but just share every thing with others. Let us also share whatever good things we have, let us share them with others.

11 - Om Arkhayanamah - Oh Sun, You are selfless, You use your entire mass for the benefit of others, You burnout yourself to give light to this world, let us also use this body to serve others. “Sareeram kadu dharma sadhanam”.

12 - Om Bhaskarayanamah - Oh Sun, You make every thing shine around you. Let us make every one around us shine and become successful in their lives. May we all shine together.

Thanks, Jyoti.

1- Om Mitrayanamah - Oh Sun, You are a friend of every one, let us all be friendly with every one like you.

2 - Om Ravayenamah - Oh Sun, You have bubbling energy, you have sustainable energy throughout the day, let us also have the same sustainable and untiring energy through out the day.

3 - Om Suryayanamah - Oh Sun, You possess only clean and positive energy inside. No pollution you cause while producing energy. Let us also possess only clean and positive energy inside.

4 - Om Bhanavenamah - Oh Sun, You shine with your own energy. Let us all shine in life with our own efforts and achievements. Let us try to be independent.

5 - Om Khagayanamah - Oh Sun, You don’t have any darkness inside, only illumination. Let us also not have any darkness inside. Let us not have any ignorance, let us have only wisdom.

6 - Om Pooshnenamah - Oh Sun, You have enormous energy and you give such a warmth for all beings, let us share only warmth to all those around us.

7 - Om Hiranyagarbhayanamah - Oh Sun, You have a gold fusion energy in the stomach. Let us also have the same fusion energy inside, consume less and produce more, eat less and convert whatever we eat into energy. Let us consume less and leave resources for the coming generations.

8 - Om Mareechayenamah - Oh Sun, You have created such a good atmosphere on the planet where all of us can live in peace and harmony, let us also create a good atmosphere around us so that every one around us can live happily.

9 - Om Adityayanamah - Oh Sun, You are the initiator, you awaken the people every day in the morning. Let us also be the initiators, let us leave our lethargy, our laziness, our boredom and let us be in the fore front of every activity in our life.

10 - Om Savitrenamah - Oh Sun, You have such generosity that you don’t keep any thing back but just share every thing with others. Let us also share whatever good things we have, let us share them with others.

11 - Om Arkhayanamah - Oh Sun, You are selfless, You use your entire mass for the benefit of others, You burnout yourself to give light to this world, let us also use this body to serve others. “Sareeram kadu dharma sadhanam”.

12 - Om Bhaskarayanamah - Oh Sun, You make every thing shine around you. Let us make every one around us shine and become successful in their lives. May we all shine together.

Thanks, Jyoti.

Friday, October 10, 2014

Monday, September 29, 2014

Xuan Wu Da Di

I am interested in the female aspect of this deity as described by Faustus Crow in the tale of Dr. Strange.

http://faustuscrow.wordpress.com/tag/xuan-wu-da-di/

Xuan Wu (玄武, lit. "Dark" or "Mysterious Warrior") is one of the higher-ranking Taoist

deities. He is revered as a powerful god, able to control the elements

and capable of great magic. He is particularly revered by martial artists and is patron saint of Hebei, Manchuria and Mongolia. As some Cantonese and Min Nan speakers (particularly Hokkien) fled into the south from Hebei with the Song dynasty, Xuan Wu is also widely revered in Fujian and Guangdong as well as among the Chinese diaspora.

Since the usurping Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty claimed the help of Xuan Wu during his successful Jingnan Campaign against his nephew, he had monasteries constructed in the Wudang Mountains of Hubei, China. where Xuan Wu allegedly attained his immortality.

He is sometimes referenced as the Dark or Mysterious Heavenly Upper Emperor or God (玄天上帝, Xuantian Shangdi) and as the Truly Martial Grand Emperor (真武大帝, Zhenwu Dadi).

One day while he was assisting a woman in labor, while cleaning the woman’s blood stained clothes along a river, the words "Xuan Tian Shang Di" appeared before him. The woman in labor turned out to be a manifestation of the goddess Guan Yin. To redeem his sins, he dug out his own stomach and intestines and washed it in the river. The river turned into a dark, murky water. After a while, it turned into pure water.

Unfortunately, Xuan Wu did indeed lose his own stomach and intestines while he washing them in the river. The Jade Emperor was moved by his sincerity and determination to clear his sins; hence he became an Immortal known with the title of Xuan Tian Shang Ti.

After he became an immortal, his stomach and intestines after absorbing the essences of the earth, it was transformed into a demonic turtle and snake which harmed people and no one could subdue them. Eventually Xuan Wu returned to earth to subdue them and later uses them as his means for transportation.

Xuan Wu is sometimes portrayed with two generals standing besides him, General Wan Gong (萬公) and General Wan Ma (萬媽). Most temples that are dedicated Xuan Wu also have Generals Wan Gong and Wan Ma, especially in Malaysia.

The two generals are deities that handles many local issues from

children's birth, medication, family matters as well as feng shui

consultation. The Malaccans

particularly in Pokok Mangga and Batu Berendam County have deep faith

in the generals due to their much good deeds and contribution to the

local villagers.

Another legend says that he borrowed the sword from Lü Dongbin to subdue a powerful demon, and after being successful, he refused to bring it back after witnessing the sword's power. The sword itself would magically return to its owner if Xuan Wu released it, so it is said that he always holds his sword tightly, and is unable to release it.

He is usually seated on a throne with the right foot stepping on the snake and left leg extended stepping on the turtle. His face is usually red with bulging eyes. His birthday is celebrated on the third day of the third lunar month.

https://heathenchinese.wordpress.com/tag/xuan-tian-shang-di/

Xuan Wu is the god of martial arts. His other names include: John Chen, Dark Lord, Xuan Tian Shang Di, and Zhen Wu Da Di. He is also the Northern Wind, and the leader of the Winds.

BACKGROUND

Xuan Wu is the creator of all martial arts. When he was Raised, the

two parts of him, the Snake and the Turtle, were left behind. They

caused havoc, killing travellers, and stealing women to keep as sex

slaves. When Xuan Wu came back, he fought the Snake and the Turtle,

absorbing them back into himself. He is the only Shen who has two

creatures. After this, he travelled the Celestial Plane, finding the

other Winds, throwing them down from their positions of power, and then

making them swear fealty to himself.

He continued his life as a Shen, until he met Michelle, a mortal woman. He married Michelle, and stayed on the Mortal Plane with her, thus draining himself of power. He had a daughter with her, named Simone. When Michelle's parents came to visit, Xuan Wu decided to travel to his Mountain on the Celestial plane, for a short while. While he was gone, a Demon Prince, named Simon Wong broke in, incapacitated Leo, Michelle's bodyguard, killed Michelle's father and brothers, and kidnapped Michelle and her mother. He seemed unaware of Simone, and so left her alone. Simon Wong was unaware of how fragile humans are, and so raped Michelle and her mother until they 'broke.' When Xuan Wu came home, he was devestated, but held it together for Simone's sake. http://kyliechan.wikia.com/wiki/Xuan_Wu

http://faustuscrow.wordpress.com/tag/xuan-wu-da-di/

Xuan Wu (god)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Since the usurping Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty claimed the help of Xuan Wu during his successful Jingnan Campaign against his nephew, he had monasteries constructed in the Wudang Mountains of Hubei, China. where Xuan Wu allegedly attained his immortality.

Contents

Other Names

Xuan Wu is also commonly known as the Northern Emperor (北帝, Modern Pinyin Beidi, Cantonese Pak Tai) and Imperial Lord (帝公, Modern Pinyin Digong, Hokkien Teh Kong).He is sometimes referenced as the Dark or Mysterious Heavenly Upper Emperor or God (玄天上帝, Xuantian Shangdi) and as the Truly Martial Grand Emperor (真武大帝, Zhenwu Dadi).

Stories

The original story

One story says that Xuan Wu was originally a prince of Jing Le State in northern Hebei during the time of the Yellow Emperor. As he grew up, he felt the sorrow and pain of the life of ordinary people and wanted to retire to a remote mountain for cultivation of the Tao.Qing Dynasty's version

Another says that Xuan Wu was originally a butcher who had killed many animals unremorsefully. As days passed, he felt remorse for his sins and repented immediately by giving up butchery and retired to a remote mountain for cultivation of the Tao.One day while he was assisting a woman in labor, while cleaning the woman’s blood stained clothes along a river, the words "Xuan Tian Shang Di" appeared before him. The woman in labor turned out to be a manifestation of the goddess Guan Yin. To redeem his sins, he dug out his own stomach and intestines and washed it in the river. The river turned into a dark, murky water. After a while, it turned into pure water.

Unfortunately, Xuan Wu did indeed lose his own stomach and intestines while he washing them in the river. The Jade Emperor was moved by his sincerity and determination to clear his sins; hence he became an Immortal known with the title of Xuan Tian Shang Ti.

After he became an immortal, his stomach and intestines after absorbing the essences of the earth, it was transformed into a demonic turtle and snake which harmed people and no one could subdue them. Eventually Xuan Wu returned to earth to subdue them and later uses them as his means for transportation.

Generals Wan Gong and Wan Ma

Zhenwu (Xuan Wu) with the two generals, and the Snake and Tortoise figures at his feet. Wudang Palace, Yangzhou

Cult

Depiction

Xuan Wu is portrayed as a warrior in imperial robes, his left hand is in the "three mountain hand seal", somewhat similar to Guan Yu's hand seal, while the right hand holds a sword, which is said to have belonged to Lü Dongbin, one of the Eight Immortals.Another legend says that he borrowed the sword from Lü Dongbin to subdue a powerful demon, and after being successful, he refused to bring it back after witnessing the sword's power. The sword itself would magically return to its owner if Xuan Wu released it, so it is said that he always holds his sword tightly, and is unable to release it.

He is usually seated on a throne with the right foot stepping on the snake and left leg extended stepping on the turtle. His face is usually red with bulging eyes. His birthday is celebrated on the third day of the third lunar month.

Xuan Tian Shang Di in Indonesia

In Indonesia, almost every Taoist temples provides an altar for Xuan Tian Shang Di. The story states that the first temple that worshiped him was a temple at Welahan Town, Jepara, Central Java. And the temples that was built in honor of him are the temple at Gerajen and Bugangan, Semarang City, Central Java. His festival is celebrated annually every the 25th day, 2nd month, of Chinese calendar.[1] The worshipers of Chen Fu Zhen Ren, especially at De Long Dian Temple, Rogojampi, Banyuwangi Regency, East Java, believes that Xuan Tian Shang Di is their patron’s spiritual teacher. That’s why they put his altar at the right side of Chen Fu Zhen Ren’s altar, in the middle room of the temple which is always reserved for the main deity of klenteng (a specific term for Chinese temple in Indonesia.Popular culture

- In the classic novel Journey to the West, Xuan Wu was a king of the north who had two generals serving under him, a "Tortoise General" and a "Snake General". This king had a temple at Wudang Mountains in Hubei, thus there is a Tortoise Mountain and a Snake Mountain on the opposite sides of a river in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei.

- In recent times, Xuan Wu is a central character in the popular urban fantasy series' by Kylie Chan: The Dark Heavens Trilogy and the Journey to Wudang Trilogy.

See also

- Black Tortoise or Turtle, the Chinese mythological figure and astronomical symbol known by the same name

References

- Buddhist Temple Jin De Yuan Jakarta. 2012. Taken= March 14th, 2013. Hian Thian Siang Te – Dewa Langit Utara

External links

- 元代以來真武信仰的另類傳播

- 玄天上帝の変容 −数種の経典間の相互関係をめぐって−

- tour de klenteng – Middle Java – Klenteng Xuan Tian Shang Di Grajen, Semarang

- Hian Thian Siang Te – God Of Northern Heaven

https://heathenchinese.wordpress.com/tag/xuan-tian-shang-di/

Xuan Wu is the god of martial arts. His other names include: John Chen, Dark Lord, Xuan Tian Shang Di, and Zhen Wu Da Di. He is also the Northern Wind, and the leader of the Winds.

BACKGROUND Edit

Edit

Xuan Wu is the creator of all martial arts. When he was Raised, the

two parts of him, the Snake and the Turtle, were left behind. They

caused havoc, killing travellers, and stealing women to keep as sex

slaves. When Xuan Wu came back, he fought the Snake and the Turtle,

absorbing them back into himself. He is the only Shen who has two

creatures. After this, he travelled the Celestial Plane, finding the

other Winds, throwing them down from their positions of power, and then

making them swear fealty to himself.

He continued his life as a Shen, until he met Michelle, a mortal woman. He married Michelle, and stayed on the Mortal Plane with her, thus draining himself of power. He had a daughter with her, named Simone. When Michelle's parents came to visit, Xuan Wu decided to travel to his Mountain on the Celestial plane, for a short while. While he was gone, a Demon Prince, named Simon Wong broke in, incapacitated Leo, Michelle's bodyguard, killed Michelle's father and brothers, and kidnapped Michelle and her mother. He seemed unaware of Simone, and so left her alone. Simon Wong was unaware of how fragile humans are, and so raped Michelle and her mother until they 'broke.' When Xuan Wu came home, he was devestated, but held it together for Simone's sake. http://kyliechan.wikia.com/wiki/Xuan_Wu

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

Tuesday, September 9, 2014

Monday, July 21, 2014

Sunday, July 20, 2014

Goddess of the Highlands

Mẫu Thượng Ngàn

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lâm Cung Thánh Mẫu (林宮聖母) or Mẫu Thượng Ngàn or Bà Chúa Thượng Ngàn (Princess of the Forest) is ruler of the Forest Palace among the spirits of the Four Palaces in Vietnamese indigenous religion.[1] In legend the Princess of the Forest was the daughter of prince Sơn Tinh and Mỵ Nương, công chúa Quế Mỵ Nương King Hung's daughter from the legend of the rivalry between Sơn Tinh and the sea god Thủy Tinh.[2] Many natural features around Vietnam feature shrines to her, such as the Suối Mỡ thermal springs area near the town of Bắc Giang.[3]Goddess of the Highlands

References

- Hy V. Luong - Tradition, Revolution, and Market Economy in a North Vietnamese ... - Page 3072010 "In Sơn-Dương, many of the non-Buddhist deities — mẫu thượng thiên (goddess of the upper sky), mẫu thượng ngàn (goddess of the highlands), mẫu Thoải (goddess of water), Hắc hổ (black tigers), etc.— were worshipped in the house.."

- Tuyé̂t Thanh Lê Phụ nữ miè̂n nam Page 12 1993 "Among the popular Goddesses, there were many famous Goddesses such as Ba Chu Thuong Ngan (Princess of Forest) who was the daughter of Son Tinh and My Nuong (King Hung's daughter). Mrs Mau Thoai was the sea King's wife who"

- Minh trị Lưu Historical remains & beautiful places of Hanoi and the surrounding area Page 268 2000 "Suối Mơ Relics is in Nghia Phương commune, Lục Ngạn district, 37 km from Bắc Giang town. It is dedicated to God of the soil, Lady Lord of Forestry princess Quế Mỵ Nương, daughter of the 16th Hùng King."

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

Lady Linshui Temple

Lady Linshui Temple

Lady Linshui Temple in Tainan. This Goddess is believed to protect fetuses and small babies.

http://photos.taiwan-guide.org/index.php/tainan-temples/lady-linshui-temple

Lady Linshui

Lady Linshui (Chen Jing-gu)

Provided by National Museum of Taiwan History

Temple of Lady Linshui

Photo by Huang Xianjin. Provided by Wordpedia.com

Lady Linshui is worshipped in Fujian (福建)

province in China as the patron goddess of women and children. She is

also known, among other names, as “Chen Jinggu (陳靖姑),” “Great Lady,”

“Shunyi furen (順懿夫人, Lady of Good Virtue)” and “Shuntian shengmu (順天聖母,

Holy Mother Who Follows the Will of Heaven).” She is also, together with

the “Second Mother Lady Lin (二媽林夫人)” and the “Third Mother Lady Li

(三媽李夫人),” one of the “Sannai furen (三奶夫人, Three Ladies).” Gazetteers and

legends from the Ming (明) Dynasty (1368–1644) and Qing (清) Dynasty

(1644–1912) tell us that Lady Linshui lived during the Dali (大曆) period

(766–779) of the Tang (唐) Dynasty (766–779) and that she followed the

Daoist teachings of the Xu Xun’s (許遜) Lushan Sect (閭山派), learning their

magical arts. She possessed the ability to exorcise demons and to drive

out evil spirits; “Killing the white snake” and “gathering the demons”

are counted among her legendary achievements. Later, Lady Linshui

rescued Fujian from a long lasting drought by giving birth while praying

for rain and thereby conjuring rain. However, she was not careful and

Changkeng ghost (長坑鬼) and other demons saw what she was up to. They took

on human shape and made their way to her family’s mansion. There they

grabbed and devoured Lady Linshui’s baby. This at once killed Lady

Linshui, who was in the middle of her conjuration. She bled to death

aged just twenty-four as her baby was eaten. As Lady Linshui died, in

the throes of difficult labor, she proclaimed: “After my death, I will

save women in difficult labor or otherwise I will not be a

goddess.”Thereafter, she was worshipped as patron goddess of pregnancy,

easing labor, raising children and expelling demons. In temples and

shrines the likenesses of the goddess are usually displayed in a seated

position and placed in a prominent position. Sometimes she is portrayed

holding a child, but in some temples she can also be found on murals and

landscape art in a prominent position, seated, wearing the robes of a

Daoist priest, holding a sword in hand, recalling her legendary killing

of the demonic snake. These two images show her dual nature, warm and

gentle, but also hard and martial.

The earliest accounts of worship of Lady Linshu can be found in Zhang Yining’s (張以寧)Yuan (元) Dynasty (1271–1368) text Shunyi Temple Inscription

(順懿廟記). The text recounts how the Song (宋) Dynasty county magistrate

Hong Tianxi (洪天錫) erected a memorial tablet to the goddess, showing that

worship of Lady Linshui dates back to the Song Dynasty. In Taiwan

worship of Lady Linshui began with the immigrant society under Qing

rule. According to Taiwanese gazetteers and historical documents the

first temple was the Linshui Temple in Baihe (白河) Township in Tainan

(臺南) County. According to an inscription on a stone stele at the side of

the temple dates from the first year of Emperor Yongzheng’s (雍正) reign

(1723).

The birthday of the goddess Lady Linshui is the 15th day of the 1st

month of the Chinese lunar calendar, that of Lady Lin is the 15th day of

the 8th month and Lady Li’s birthday is the 9th day of the 9th. The

most significant ritual activities related to the Three Ladies take

place on these dates and various temples, such as the Fenxiang (分香)

Temples, Fenling (分靈) Temples, Jiaotou Temples (角頭廟) and the local

temples of the interacting boundaries (交陪境) all participate. The

activities to promote fellowship between the various temples and their

deities reveal much of the power structures between local temples.

Rituals to protect children from demons, fertility rituals (栽花換斗), the

coming of age ceremony for sixteen year-olds (做十六歲) and adopting sons

are all ceremonial activities that commonly take place in these temples.

Copyright © 2011 Council for Cultural Affairs. All Rights Reserved.

English Keyword

Guan Yu , Three Kingdoms , Sacred Emperor of balancing literacy , Teacher of Shanxi Province

Guan Yu , Three Kingdoms , Sacred Emperor of balancing literacy , Teacher of Shanxi Province

References

- He, Qiaoyuan. (1995). Min shu, Vol.1-5 [閩書(五冊)]. Ba min wen xian cong kan. Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing House.

- Huang, Zhongzhao. (Ed.). (1991). Ba min tong zhi, Vol.1-2 [八閩通志(兩冊)]. Fu jian di fang zhi cong kan. Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing House.

- Lin, Xianji., et al. (1967). Gu tian xian zhi [古田縣志]. Zhong guo fang zhi cong shu, No. 100. Taipei: Cheng Wen Publishing Co., Ltd.

- He, Qiuzuan. (1987). Min dou bie ji, Vol.1-3 [閩都別記(三冊)]. Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing House.

- Xie, Jinluan. (Ed.). (1977). Xu xiu tai wan xian zhi [續修臺灣縣志]. Tai wan wen xian shi liao cong kan di er ji, No. 32. Taipei: Datong Bookstore.

Lady Linshui

Classification:Religion > Worship and Religion > Orthodox Deities > Lady Linshui

臨水夫人

Contributor: Kang Shihyu

http://taiwanpedia.culture.tw/en/content?ID=4428

Lady Linshui Temple

Lady Linshui Temple (Línshuǐ Fūrén Miào 臨水夫人廟)

Right next door to the Koxinga Shrine is the Lady Linshui Temple (also called Madame Linshuei Temple, or Lady of Linshui Ma Temple). This is a largely feminine temple that focuses on the cult of Lady Linshui, the Goddess of Birth and Fertility. While many temples around Tainan feature the goddess idols of Guanyin and Matsu, no other temple has as many female idols or depictions of women as the Lady of Linshui Temple.

http://tainancity.wordpress.com/2010/11/06/lady-linshui-temple/

The Lady of Linshui

A majority of the next blog entries will be about:

The Lady of Linshui: A Chinese Female Cult

Brigitte Baptandier, The Lady of Linshui: A Chinese Female Cult, trans. Kristin Ingrid Fryklund (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008)

"This anthropological study examines the cult of the Chinese goddess Chen Jinggu, divine protector of women and children. The cult of the "Lady of Linshui" began in the province of Fujian on the southeastern coast of China during the eleventh century and remains vital in present-day Taiwan. Skilled in Daoist practices, Chen Jinggu's rituals of exorcism and shamanism mobilize physiological alchemy in the service of human and natural fertility. Through her fieldwork at the Linshuima temple in Tainan (Taiwan) and her analysis of the narrative and symbolic aspects of legends surrounding the Lady of Linshui, Baptandier provides new insights into Chinese representations of the feminine and the role of women in popular religion."

http://www.sup.org/book.cgi?id=4857 -- Source

"Brigitte Baptandier is Director of Research at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), in the Laboratoire d'ethnologie et de Sociologie comparative, at Université Paris X, Nanterre, where she teaches Chinese anthropology. She also teaches at the Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO) in Paris."

# Religion — Asian

# Anthropology — Asia

# Asian Studies

Series link: # Asian Religions and Cultures #shaman

Brigitte Baptandier, The Lady of Linshui: A Chinese Female Cult, trans. Kristin Ingrid Fryklund (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008)

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Nanguan Music

Nanguan (music)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nanguan (Chinese: 南管; pinyin: nánguǎn; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: lâm-im; literally: "southern pipes", also called nanyin (南音), nanyue (南樂), or nanqu (南曲)) is a style of Chinese classical music originating in the southern Chinese province of Fujian (福建), and is also now highly popular in Taiwan, particularly Lukang.[1]Fujian is a mountainous coastal province of China. Its provincial capital is Fuzhou, while Quanzhou was a major port in the 7th century CE, the period between the Sui and Tang eras. Situated upon an important maritime trade route, it was a conduit for elements of distant cultures. The result was what is now known as nanguan music, which today preserves many archaic features.

It is a genre strongly associated with male-only community amateur musical associations (quguan or "song-clubs"), each formerly generally linked to a particular temple, and is viewed as a polite accomplishment and a worthy social service, distinct from the world of professional entertainers.[1] It is typically slow, gentle, delicate and melodic, heterophonic and employing four basic scales.[2]

Styles and instruments

Nanguan repertory falls into three overlapping styles, called zui, po and khiok (zhi, pu and qu in Mandarin), differentiated by the contexts in which they occur, by their function, the value accorded them by musicians and by their formal and timbral natures. The Zui (指) is perceived as the most "serious" repertoire: it is a purely instrumental suite normally more than thirty minutes in length, of two to five sections usually, each section being known as a cu or dei ("piece"). Each is associated with a lyric that alludes to a story but, although this may denote origins in song or opera, today zui is an important and respected instrumental repertory. However, the song text significantly eases the memorising of the piece.Khiok (曲) is a vocal repertory: two thousand pieces exist in manuscript. It is lighter and less conservative in repertory and performance than zui. Most popular pieces today are in a fast common metre and last around five minutes. Po (譜) literally means "notation" - these are pieces that have no associated texts and thus must be written down in gongchepu notation. It is an instrumental style that uses a wider range than zui and that emphasises technical display.[3]

A nanguan ensemble usually consists of five instruments. The pie (muban (木板) or wooden clapper) is usually played by the singer. The other four, known as the dinxiguan or four higher instruments, are the four-stringed lute (gibei, pipa (琵琶) in Mandarin), a three-stringed, fretless, snakeskin-headed long-necked lute that is the ancestor of the Japanese shamisen, called the samhen, (sanxian (三線) in Mandarin), the vertical flute, (xiao (簫), also called dongxiao), and a two-stringed "hard-bowed" instrument called the lihen, slightly differing from the Cantonese erxian. Each of the four differs somewhat from the most usual modern form and so may be called the "nanguan pipa" etc. Each instrument has a fixed role. The gibei provides a steady rhythmic skeleton, supported by the samhen. The xiao, meanwhile, supplemented by the lihen, puts "meat on the bones" with colourful counterpoints.[3]

These instruments are essential to the genre, while the eixiguan or four lower instruments are not used in every piece. These are percussion instruments, the chime (hiangzua), a combined chime and wood block called the giaolo, a pair of small bells (xiangjin) and a four-bar xylophone, the xidei. The transverse flute called the pin xiao (dizi in Mandarin) and the oboe-like aiya or xiao suona are sometimes added in outdoor or ceremonial performances. When all six combine with the basic four, the whole ensemble is called a zayim or "ten sounds".[3]

Diaspora

From the 17th century the Hoklo immigrated from Fujian to Taiwan and took with them informal folk music as well as more ritualized instrumental and operatic forms taught in amateur clubs, such as beiguan and nanguan. Large populations of similar background can also be found in Malaysia, Guangdong, Hong Kong, Philippines, Singapore, Burma, Thailand and Indonesia, where they are usually referred to as Hokkien, ("Fujian" in the Min Nan language). There are two nanguan associations in Singapore[4] and formerly there were several in the Philippines: Tiong-Ho Long-Kun-sia is one that is still active. Gang-a-tsui and Han-Tang Yuefu have popularised the nanguan ensemble abroad. A Quanzhou Nanguan Music Ensemble was founded in the early 1960s, and there is a Fuzhou Folk Music Ensemble, founded in 1990.References

- Wang, Ying-Fen (September 2003). "Amateur Music Clubs and State Intervention: The Case of Nanguan Music in Postwar Taiwan". Journal of Chinese Ritual, Theatre and Folklore (141). Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- Wang, Xinxin. "Nanguan Music: Appreciation and Practice (course description)". Graduate Institute of Musicology, National Taiwan University. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010.

- Chou, Chenier. "Nanguan Music". University of Sheffield. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007.

- Koh, Sze Wei (May 30, 2006). "Nan Yin — A Historical Perspective". Save Our Chinese Heritage. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

External links

Video

- Nanguan videos

- Nanguan videos http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanguan_%28music%2

- http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/833866?uid=3738392&uid=2129&uid=2&uid=70&uid=4&sid=21104323447153

The Music of Nanguan - Lin PoChiThe Lâm-koán is called “Nanyin”(南音) in southeastern China and “Nanyue”(南樂) in southeastern Asia. It used to be popular in locations where the Minnan language was spoken including Quanzhou and Xiamen. It then came to Taiwan around the Ming Dynasty and followed the prevalence of Taiwanese migration communities in southeastern Asia. Lâm-koán’s current style of singing preserves that of ancient times. It is sung with the accent of Quanzhou so it is also therefore named “Chôan-Chiu Hiân-koán”(泉州絃管). Modern Lâm-koán performances have preserved the form of Daqu (大曲) in the Tang Dynasty. The main parts of the ensemble are called “Siau-koán”(簫管) or “Téng-sì-koán”(上四管) meaning “the core four parts” collectively.When “Téng-sì-koán” plays with “Ē-sì-koán”(下四管, translated as “the peripheral four parts”) and “Ài-á”(噯子), it is called “Sỉp-im”(十音).

Many scholars argue that the music of Lâm-koán is a “living fossil” of Chinese music. The fact that the Lâm-koán singer holds the “Phek” to direct the ensemble has proved that the tradition of “Siang-Ho Ker”(“相和歌”) of the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) still remains. The construction of instruments (such as Pê, Jī-hiân, Tōng-siau and others) also preserved Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) styles. Furthermore, titles of Lâm-koán repertoire are often from poems and names of tunes that already existed. This living fossil or living tradition of Lâm-koán is still taught with oral instruction in Taiwan and has a distinct difference from the Chinese style.

The music aesthetics of Lâm-koán music found its base from concepts of Chinese literature and Taoism. Music starts from morality, and in the ensemble the concepts of “Five elements” (五行) and “Yin and Yang”(陰陽) are apparent. For example the five parts of Téng-sì-koán (Siau, Jī-hiân, Sam-hiân, Pê, and Phek) are seated in order and clockwise. The percussive tone color of Pê and Sam-hiân are strong like “Yang”, and the linear and continual tone color of Siau and Jī-hiân are soft like “Yin”. The mixture of the percussive and linear tone colors represents the complimentary “Yin and Yang”. In the ensemble of Téng-sì-koán and Ē-sì-koán, the principle ”Metal Controls Wood” (“金木相剋”) is adopted; therefore, metallic and wooden instruments are played in alteration. The presentation of music emphasis is not on individual techniques but the tacit understanding among all parts. Thus, the Sam-hiân follows the Pê like a shadow, and the Jī-hiân fills in for the leading instrument Siau which requires occasional breathing. Both Sam-hiân and Jī-hiân do not surpass their leading parts.Instrumentation

1. Phek: made of five long pieces of wood, held by the singer who strikes the Phek on every beat to control the tempo.2. Pê: aka Nanguan Phi-pha, the leading part of the ensemble. It has a curved-neck like the Tang and Song Phi-pha, but unlike the modern Phi-pha, it is played horizontal. It has four bars and ten frets on the fingerboard with four strings tuned d-g-a-d1 (工、士、下、工).3. Sam-hiân: its resonance box is covered with snake skin on both sides. Unlike Pê its neck has no frets. Its three strings are tuned A-d-a (下、工、一). Its fingerings are the same as those of Pê’s and sounds an octave lower than Pê.4. Jī-hiân: The Jī-hiân stick is made from bamboo and usually has 13 nodes. One must follow certain strict rules when selecting the bamboo material for Jī-hiân. The resonant box is made from the root of the Pandan (Nâ-tâo) tree. Its pegs are on the same side as the strings. The strings are silk and tuned to g- d1(士、工). Its bow is soft.5. Siau: It is made from the root of bamboo. It has 10 flats and 9 nodes within the length of 1 “meter” and 8 “inch” of Tang (唐制一尺八寸, about 54 cm). The lowest pitch is d1 (「工」).6. Híun-tsóan: A tiny gong hung from a small bamboo frame and struck with a small padded mallet. Its rhythm is basically the same as that of Pê except that it rests on the beats that the Phek strikes(金木相剋).7. Sì-tè: also called “Sì -pó”, meaning “four treasures”. The Sì-tè player holds two clappers in each hand. It plays quickly and in vibration to reflect the Pê’s tremolo or strikes once to reflect the Phek’s beat. The tacit part of its rhythm is the same as that of Pê’s.8. Siang-im: Also named “Siang-tseng” or “Siang-lêng”, the player avoids playing on the beat.9. Kiò-lô: Consisting of a small gong and a temple block. The gong is usually played one-half beat after the Híun-tsóan, and the temple block usually falls on the downbeats.10. Aì-á: A small Sōna, also called “giok-aì”. It appears in the “Sip- im” ensemble. It is never played in a loud dynamic but “sings” softly as a person does when singing Lâm-koán.The Lâm-koán music is divided into “Tsuín” (指), “Kheh” (曲) and “Phóo” (譜). “Tsuín” and “Kheh” both have lyrics; however, the lyrics of “Tsuín” are only for the purpose of memorizing the music and not sung in performances. “Kheh” is the center part of all activities in Lâm-koán. “Phóo” is purely instrumental. In a concert, the music must follow the order of “Starting with Tsuín”, “Into Kheh”, and “Ending with Phóo” (起指、落曲、煞譜).© TNUA School of Music Department of Traditional Music | TEL: 02-2893-8247 | FAX: 02-2893-8748 http://trd-music.tnua.edu.tw/en/intro/c.html

Taiwan Journey Part One: Nanguan Music with Wu Hsin-fei

https://vimeo.com/13859136 This performance is amazing!http://www.culture.tw/index.php?option=com_sobi2&sobi2Task=sobi2Details&sobi2Id=326&Itemid=175

| Wang Xinxin infuses ancient nanguan music with fresh energy | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||||

| 28 August 2007 | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Nanguan’s reluctant innovator

Wang Xinxin, lauded as one of the foremost practitioners of nanguan music, is receiving international recognition with concert and lecture tour of Europe

By Ian Bartholomew / Staff reporter

Nanguan (南管), an ancient style of Chinese music that has seen a

gradual revival over the last couple of decades, is about simplicity —

the kind of simplicity that can only be achieved by a lifetime of

dedication. Wang Xinxin (王心心), the founder of the Xinxin Nanguan

Ensemble (心心南管樂坊), has established herself as one of the foremost

exponents of nanguan music on the contemporary scene, and her

achievements are being given international scholarly recognition in a

concert and lecture tour to Paris, Lisbon and Heidelberg later this

week.The origins of nanguan are lost in the mists of time, but by the end of the first millennium, it was already associated with China’s southern province of Fujian, particularly to the then prosperous port of Quanzhou (泉州). The word nanguan translates as “southern pipes,” and its primary development has been in the form of chamber music, usually a quartet, sometimes with vocal accompaniment. It is particularly known for its extremely slow thematic exposition, a feature that has made it a hard sell to contemporary audiences.

Wang’s love of nanguan’s almost meditative simplicity is at odds with her role as a performing artist in contemporary Taiwan. Nanguan’s roots in amateur musical associations in which musicians performed primarily for their own pleasure have created obstacles for its development as a public entertainment. Taiwan’s Han Tang Yuefu (漢唐樂府), one of the first groups to develop nanguan as a theater event, derives much of its impact from creating lavish visual settings that provide a feast for the eyes when the slow pace of the music leaves audiences floundering.

Wang, a Quanzhou native and former member of Han Tang Yuefu, established her own company in 2002 to pursue a different vision. Her productions are not without theatrical elements, for as she admitted — with regret — this is the only way nanguan can survive as a performance art in the modern world.

Speaking of the art of nanguan singing, Wang said “the performer should not respond to any of the emotions expressed in the lyrics. Everything is expressed through tone, timbre, and other aspects of musical expression. Every hint of theatricality should be banished. In nanguan, we talk about going to ‘hear’ a show, not to ‘see’ a show. Many people at a nanguan performance may even sit there with their eyes closed, their bodies moving trancelike with the music.”

The stage effects and narrative links in Wang’s shows are intended to provide a doorway into the music.

“We try to create a meditative atmosphere through our stage settings. In some respects, you might almost say it adds to a performance. It sets the mood for the audience; the visual elements aim to sooth and calm their emotions before the music begins. If they had to get straight into the music, for modern audiences, this would be very difficult,” Wang said.

Wang’s main interests are in fusing nanguan with classic Chinese poetry, adding to the music’s already heavily literary associations, especially with the great romantic tales of Chinese literature (which almost invariably end in tragedy). She is also interested in exploring musical possibilities in combination with other instruments. In the case of her current tour, she has joined together with guqin (古琴) master Huang Chin-hsin (黃勤心). The combination of nanguan music and guqin is a radical departure from tradition, though perhaps not particularly obvious to outsiders.

Wang sees herself very much as an innovator, and sees plenty of potential for innovation from within the Chinese tradition, a refreshing change from the monotonous refrain about East-West fusion that dominates Taiwan’s arts establishment and seems to be the key to government funding.

Still, Wang has not completely escaped the need to conform to contemporary cultural dogma, and has ventured into collaborations with multimedia. As a professional company, the demand for visual stimulation is ineluctable. Costumes, projected backgrounds, stage sets and narrative links have all been included in some of Wang’s shows. “What people don’t always understand is that things that seem simple, such as a group of musicians playing music in a bare performance space, takes years of dedication and also costs money,” she said.

Although Wang has proved reasonably successful in accessing the limited government funds and somewhat more generous corporate sponsorship available, there is a sense of regret that nanguan needs to become such a circus. Wang has established monthly small venue performances at her studio and at the Taipei’s Dadaocheng Theater (大稻埕戲苑), where her stripped down style of nanguan is given a regular airing.

Wang’s unwavering focus on the more abstruse appeal of music over showy oriental exoticism has kept the Xinxin Nanguan Ensemble small, but it has won considerable respect from curators of international arts festivals, particularly in Europe. On her current tour, Wang will speak at the Sorbonne in Paris (Sept. 14) and at the Maison des Cultures du Monde (Sept. 15) about preserving cultural traditions in a contemporary context, and perform at the Orient Museum in Lisbon (Sept. 17), the Musee Guimet in Paris(Sept. 25) and the French Senate House in Paris (Sept. 26).

http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2012/09/10/2003542387/1

Nanguan music is important in the areas that worship Chen Jinggu.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)