http://www.esoteric.msu.edu/VolumeVI/Dao.htm

Bibliography

Bardon, Franz. The Key to the True Quabbalah: The Quabbalist as a Sovereign in the Micro- and the Macrocosm (Germany: Wuppertal, 1975).

Ballantyne, Edmund. “Alan Watts.” In Charles Lippy (ed.) Twentieth-Century Shapers of American Popular Religion (NY: Greenwood Press, 1989).

Bjerregaard, C. H. A. The Inner Life and the Tao-Teh-King (New York: The Theosophical Publishing Co., 1912).

Blofeld, John. The Book of Change: A New Translation of the Ancient Chinese I Ching ( NY: Dutton 1966).

Blofeld, John. Taoist Mysteries and Magic (Boston, MA: Shambala Press, 1973).

Blofeld, John. Taoism: The Road to Immortality (Boston, MA: Shambala Press, 1978).

Burckhardt, Titus. Sacred Art Art in East and West: It’s Principles and Methods (London: Perennial Books, 1967).

Capra, Fritjof. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism (Boulder, CO: Shambala Press, 1975).

Carus, Paul. Lao-Tze's Tao-Teh-King: Chinese-English, with Introduction, Transliteration, and Notes (Chicago: Open Court Publishing Company, 1898).

Carus, Paul and Teitaro Suzuki (eds). T`ai-shang kan-ying p`ien : Treatise of the Exalted One on Response and Retribution (Chicago, IL: Open Court Pub. Co., 1906).

45

Chalmers, John. The Speculations on Metaphysics, Polity, and Morality, of "the Old Philospher," Lau-Tsze (London, Trübner & Co., 1868).

Chang, Chung-yuan. "An Introduction to Taoist Yoga". The Review of Religion Vol: 20: 131-148. (Reprinted in Laurence G. Thompson (ed.) The Chinese Way in Religion (CA: Dickenson, 1973: 63-76.).

Clarke, J. J. The Tao of the West: Western Transformations of Taoist Thought (London: Routledge Press, 2000.)

Cooper, J. C. Taoism: The Way of the Mystic (Wellingborough, England: The Aquarian Press, 1972).

Crowley, Aleister. Shih Yi; A Critical and Mnemonic Paraphrase of the Yi King (Oceanside, CA: H. P. Smith, 1971).

Crowley, Aleister. Liber XXI: Khing Kang King, The Classic of Purity (Kings Beach, CA: Thelema Publications, 1973). [Orig. 1939]

Culling, Louis. The Pristine Yi King: Pure Wisdom of Ancient China (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1989).

Davis, Tenney L. "The Identity of Chinese and European Alchemical Theory." Journal of Unified Science (Erkenntnis), 1939 Vol. 9: 7-12.

Deng Ming-Dao. Scholar Warrior : An Introduction to the Tao in Everyday Life (San Francisco, CA: Harper SanFrancisco, 1990).

Deng, Ming-Dao. Chronicles of Tao : The Secret Life of a Taoist Master (San Francisco, CA: Harper SanFrancisco, 1993).

Drury, Neville. The History of Magic in the Modern Age: A Quest for Personal Transformation (NY: Carroll & graf Publishers, 2000).

Evola, Julius. Taoism: The Magic, The Mysticism (Eugene, WA: Oriental Classics, Holmes Publishing Group, 1995).

Faivre, Antoine. Access to Western Esotericism (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1994).

Faivre, Antoine. “Renaissance Hermeticism and Western Esotericism.” In Roelof van den Broek and Wouter J. Hanegraaff (eds.), Gnosis and Hermeticism fromAntiquity to Modern Times (Albany NY: State University of New York Press, 1998).

Ferrer, Jorge N. Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory Vision of Human Spirituality (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2002).

Girardot, N. J. Myth and Meaning in Early Taoism: The Theme of Chaos (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1983).

Goddard, Dwight. Laotzu's Tao and Wu Wei; Dao De Jing. (NY: Brentano, 1919).

Guénon, René. The Great Triad ( (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1994). [Orig: 1946].

Guénon, René. Symbolism of the Cross. (London: Luzac, 1958).

Guénon, René. “Al-Faqr or`Spiritual Poverty'” In Studies in Comparative Religion, Winter 1973:16-20. <http://kataragama.org/al-faqr.htm>

Guénon, René. Insights into Islamic Esoterism & Taoism (Aperçus sur l'ésotérisme islamique et le taoïsme, Paris 1973) (Ghent, NY : Sophia Perennis, 2001).

Huang, Al Chung-liang. Embrace Tiger, Return to Mountain: The Essence of T`ai Chi (Moab, UT: Real People Press, 1973).

Henderson, John. The Development and Decline of Chinese Cosmology (NY: Columbia University Press, 1984).

Herman, J. R. I and Tao: Martin Buber’s Encounter with Chuang Tzu (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996).

Irwin, Lee. "Western Esotericism, Eastern Spirituality, and the Global Future,” Esoterica, Vol. III, 2001:1-47.

Johnson, Obed Simon. A Study of Chinese Alchemy (Shanghai, China, 1928).

Johnson, Samuel. Oriental Religions and their Relation to Universal Religion (Boston, MA: Houghton, Osgood and Company, 1878).

Jones, David and John Culliney. “The Fractal Self and the Organization of Nature: The Daoist Sage and Chaos Theory.” In Zygon, Vol. 34/4:643-654.

Keane, Lloyd. Magick/Liber Aba and Mysterium Coniunctionis: A Comparison of the Writings of Aleister Crowley and C.G. Jung MA Thesis, Carelton University. <http://www.geocities.com/nuhad418/ JungCrowley.htm>

King, Richard.

Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and "the Mystic East" (CA: Routledge Press, 1999).

Kirkland, Russell. “The Historical Contours of Taoism in China: Thoughts on Issues of Classification and terminology.” Journal of Chinese Religion Vol. 25/1 1997:57-76.

Le Forestier, René. L'occultisme en France aux XIXème et XXème isècles (inédit par Antoine Faivre, Milano: Archè, 1990).

Legge, James. The Religions of China; Confucianism and Tâoism Described and Compared with Christianity (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1881).

Lewis, Dennis. The Tao of Natural Breathing: For Health, Well-Being, and Inner growth (San Francisco, CA: Mountain Wind Publishing, 1997).

Lu, K'uan Yü. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation; Self-cultivation by Mind Control as Taught in the Ch'an Mahayana and Taoist Schools in China (London: Rider, 1964).

46

Lu, K'uan Yü. Taoist Yoga: Alchemy and Immortality (NY: Samuel Weiser, 1972).

Ni, Hua Ching. The Taoist Inner View of the Universe and the Immortal Realm (Santa Monica, CA: College of Tao & Traditional Chinese Healing, 1979/1996).

Ni, Hua Ching. The Esoteric Teachings of the Tradition of Tao (Malibu, CA: Shrine of the Eternal Breath of Tao, 1989).

Ni, Hua Ching. Esoteric Tao Teh Ching (Santa Monica, CA: College of the Tao & Taditional Chinese Healing, 1992).

Ni, Hua-Ching. Concourse of All Spiritual Paths : East Meets West, Modern Meets Ancient (Santa Monica, CA: Seven Star Communications, 1995).

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. Knowledge and the Sacred (NY: State University of New York Press: 1990).

Parks, Graham (ed.) Heidegger and Asian Thought (Honolulu: University of Honolulu Press, 1987).

Rawlinson, Andrew. “A History of Western Sufism.” Diskus Vol 1:1 1993:45-83. <http:// www.uni-marburg.de/religionswissenschaft/journal/diskus/rawlinson.html>

Robinet, Isabelle. Taoism: Growth of the Religion (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997).

Rosen, David and Ellen Crouse. “The Tao of Wisdom: Integration of Taoism and the Psychologies of Jung, Erikson, and Maslow.” In Polly Young-Eisendrath and Melvin Miller (eds.) The Psychology of Mature Spirituality (Philadelphia, PA: Routledge Press, 2001: 120-129).

Saso, Michael. Taoist Master Chuang (Eldorado Springs, CO: Sacred Mountain Press, 2000). [Origin: 1978].

Schipper, Kristofer. The Taoist Body (Berkeley, CA: Universiyt of California Press, 1993).

Schuon, Frithjof. Transcendent Unity of Religions (IL: Quest Books, 1984).

Sedgwick, Mark. “Traditionalist Sufism.” Aries Vol. 22, 1999: 3-24. <http:// www.aucegypt.edu/faculty/sedgwick/tradsuf.htm#N_4_>.

Smith, Huston. Forgotten Truth: The Primordial Tradition (NY: Harper Colophon Books, 1977).

Strickmann, Michael. “On the Alchemy of T’ao Hung-ching.” In Holmes Welch and Anna Seidel (eds.), Facets of Taoism: Essays in Chinese Religion (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 1979: 123-192).

Towler, Solala. A Gathering of Cranes: Bring the Tao to the West (Eugene, OR: Abode of the Eternal Tao, 1996).

Waterfield, Robin. René Guénon and the Future of the West : The Life and Writings of a 20th-century Metaphysician (Wellingborough, England: Crucible, 1987).

Watts, Alan. The Supreme Identity: An essay on Oriental Metaphysics and Christian Religion (NY: Pantheon, 1950).

Watts, Alan. The Wisdom of Insecurity (NY: Pantheon, 1951).

Watts, Alan. Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown (NY: Random House, 1968).

Watts, Alan. Tao: The Watercourse Way (NY: Panteon Books, 1975).

Wilhelm, Richard. The Secret of the Golden Flower, with commentary by C. G. Jung (London, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., 1931).

Wieger, Léon. Chinese Characters, Their Origin, Etymology, History, Classification and Signification (Hsien-hsien, Catholic Mission Press, 1927a).

Wieger, Léon. A History of the Religious Beliefs and Philosophical Opinions in China from the Beginning to the Present Time (Hsien-hsien Catholic Mission Press, 1927b).

Wong, Eva. The Shambhala Guide to Taoism (Boston, MA: Shambhala Press, 1997).

Yudelove, Eric. The Tao & the Tree of Life: Alchemical & Sexual Mysteries of the East and West (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1995).

Yudelove, Eric. Taoist Yoga and Sexual Energy (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2000).

Daoist meditation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Daoist meditation | |||

| Chinese | 道家冥想 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | Dao school deep thinking | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Portal Taoism |

Daoist meditation refers to the traditional meditative practices associated with the Chinese philosophy and religion of Daoism, including concentration, mindfulness, contemplation, and visualization. Techniques of Daoist meditation are historically interrelated with Buddhist meditation, for instance, 6th-century Daoists developed guan 觀 "observation" insight meditation from Tiantai Buddhistanapanasati "mindfulness of breath" practices.

Traditional Chinese medicine and Chinese martial arts have adapted certain Daoist meditative techniques. Some examples areDaoyin "guide and pull" breathing exercises, Neidan "internal alchemy" techniques, Neigong "internal skill" practices, Qigongbreathing exercises, Zhan zhuang "standing like a post", and Taijiquan "great ultimate fist" techniques.

Contents

[hide]Terminology[edit]

The Chinese language has several keywords for Daoist meditation practices, some of which are difficult to translate accurately into English.

Types of meditation[edit]

Livia Kohn (2008a:118) distinguishes three basic types of Daoist meditation: "concentrative", "insight", and "visualization".

Ding 定 literally means "decide; settle; stabilize; definite; firm; solid" and early scholars such as Xuanzang used it to translateSanskrit samadhi "deep meditative contemplation" in Chinese Buddhist texts. In this sense, Kohn (2008c:358) renders ding as "intent contemplation" or "perfect absorption." The Zuowanglun has a section called Taiding 泰定 "intense concentration"

Guan 觀 basically means "look at (carefully); watch; observe; view; scrutinize" (and names the Yijing Hexagram 20 Guan "Viewing").Guan became the Daoist technical term for "monastery; abbey", exemplified by Louguan 樓觀 "Tiered Abbey" temple, designating "Observation Tower", which was a major Daoist center from the 5th through 7th centuries (see Louguantai). Kohn (2008d:452) says the word guan, "intimates the role of Taoist sacred sites as places of contact with celestial beings and observation of the stars."Tang Dynasty (618–907) Daoist masters developed guan "observation" meditation from Tiantai Buddhist zhiguan 止觀 "cessation and insight" meditation, corresponding to śamatha-vipaśyanā – the two basic types of Buddhist meditation are samatha "calm abiding; stabilizing meditation" and vipassanā "clear observation; analysis". Kohn (2008d:453) explains, "The two words indicate the two basic forms of Buddhist meditation: zhi is a concentrative exercise that achieves one-pointedness of mind or" cessation" of all thoughts and mental activities, while guan is a practice of open acceptance of sensory data, interpreted according to Buddhist doctrine as a form of "insight" or wisdom." Guan meditators would seek to merge individual consciousness into emptiness and attain unity with the Dao.

Cun 存 usually means "exist; be present; live; survive; remain", but has a sense of "to cause to exist; to make present" in the Daoist meditation technique, which both theShangqing School and Lingbao Schools popularized.

Other keywords[edit]

Within the above three types of Daoist meditation, some important practices are:

- Zuowang 坐忘 "sitting forgetting" was first recorded in the (c. 3rd century BCE) Zhuangzi.

- Shouyi 守一 "guarding the one; maintaining oneness" involves ding "concentrative meditation" on a single point or god within the body, and is associated with Daoist alchemical and longevity techniques (Kohn 1989b). According to Master and Dr. Zhi Gang Sha, Shouyi means "foucs on Jin Dan".[1] Jin Dan is a golden light ball that the Daoists visualize during the meditation practices. Jin Dan can be formed in a human body when the meditators are able to use the mind power of practising conscious concentration to a degree that "matter, energy, and souls join as one" during the meditation process.[2]

- Neiguan 內觀 "inner observation; inner vision" is visualizing inside one's body and mind, including zangfu organs, inner deities, qi movements, and thought processes.

- Yuanyou 遠遊 "far-off journey; ecstatic excursion", best known as the Chuci poem title Yuan You, was meditative travel to distant countries, sacred mountains, the sun and moon, and encounters with gods and xian transcendents.

- Zuobo 坐缽 "sitting around the bowl (water clock)" was a Quanzhen School communal meditation that was linked to Buddhist zuochan (Japanese zazen) 坐禪 "sitting meditation"

Warring States period[edit]

The earliest Chinese references to meditation date from the Warring States period (475-221 BCE), when the philosophical Hundred Schools of Thought flourished.

Guanzi[edit]

Four chapters of the Guanzi have descriptions of meditation practices: Xinshu 心術 "Mind techniques" (chapters 36 and 37), Baixin 白心 "Purifying the mind" (38), and Neiye 內業 "Inward training" (49). Modern scholars (e.g., Harper 1999:880, Roth 1999:25) believe the Neiye text was written in the 4th century BCE and the others were derived from it. A. C. Graham (1989:100) regards the Neiye as "possibly the oldest 'mystical' text in China"; Harold Roth (1991:611-2) describes it as "a manual on the theory and practice of meditation that contains the earliest references to breath control and the earliest discussion of the physiological basis of self-cultivation in the Chinese tradition." Owing to the consensus that proto-Daoist Huang-Lao philosophers at the Jixia Academy in Qi composed the core Guanzi, Neiye meditation techniques are technically "Daoistic" rather than "Daoist" (Roth 1991).

Neiye Verse 8 associates dingxin 定心 "stabilizing the mind" with acute hearing and clear vision, and generating jing 精 "vital essence". However, thought, says Roth (1999:114), is considered "an impediment to attaining the well-ordered mind, particularly when it becomes excessive."

Verse 18 contains the earliest Chinese reference to practicing breath-control meditation. Breathing is said to "coil and uncoil" or "contract and expand"', "with coiling/contracting referring to exhalation and uncoiling/expanding to inhalation" (Roth 1991:619).

Neiye Verse 24 summarizes "inner cultivation" meditation in terms of shouyi 守一 "maintaining the one" and yunqi 運氣 "revolving the qi". Roth (1999:116) says this earliest extant shouyi reference "appears to be a meditative technique in which the adept concentrates on nothing but the Way, or some representation of it. It is to be undertaken when you are sitting in a calm and unmoving position, and it enables you to set aside the disturbances of perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and desires that normally fill your conscious mind."

Daodejing[edit]

Several passages in the classic Daodejing are interpreted as referring to meditation. For instance, "Attain utmost emptiness, Maintain utter stillness" (16, tr. Mair 1994:78) emphasizes xu 虛 "empty; void" and jing 靜 "still; quiet", both of which are central meditative concepts. Randal P. Peerenboom (1995:179) describes Laozi's contemplative process as "apophatic meditation", the "emptying of all images (thoughts, feelings, and so on) rather than concentration on or filling the mind with images", comparable with Buddhist nirodha-samapatti "cessation of feelings and perceptions" meditation.

Verse 10 gives what Roth (1999:150) calls the "probably the most important evidence for breathing meditation" in the Daodejing.

Three of these Daodejing phrases resonate with Neiye meditation vocabulary. Baoyi 抱一 "embrace unity" compares with shouyi 守一 "maintain the One" (24, Roth 1999:92 above). Zhuanqi 專氣 "focus your vital breath" is zhuanqi 摶氣 "concentrating your vital breath" (19, tr. Roth 1999:82). Dichu xuanjian 滌除玄覽 "cleanse the mirror of mysteries" and jingchu qi she 敬除其舍 "diligently clean out its lodging place" (13, Roth 1999:70) have the same verb chu "eliminate; remove".

The Daodejing exists in two received versions, named after the commentaries. The "Heshang Gong version" (see below) explains textual references to Daoist meditation, but the "Wang Bi version" explains them away. Wang Bi (226-249) was a scholar of Xuanxue "mysterious studies; neo-Daoism", which adapted Confucianism to explain Daoism, and his version eventually became the standard Daodejing interpretation. Richard Wilhelm (tr. Erkes 1945:122) said Wang Bi's commentary changed the Daodejing "from a compendiary of magical meditation to a collection of free philosophical aperçus."

Zhuangzi[edit]

The (c. 4th-3rd centuries BCE) Daoist Zhuangzi refers to meditation in more specific terms than the Daodejing. Two well-known examples of mental disciplines are Confuciusand his favorite disciple Yan Hui discussing xinzhai 心齋 "heart-mind fasting" and zuowang "sitting forgetting" (Roth 1991:602). In the first dialogue, Confucius explains xinzhai.

In the second, Yan Hui explains zuowang meditation.

Roth (1999:154) interprets this "slough off my limbs and trunk" (墮肢體) phrase to mean, "lose visceral awareness of the emotions and desires, which for the early Taoists, have 'physiological' bases in the various organs." Peerenboom further describes zuowang as "aphophatic or cessation meditation."

Another Zhuangzi chapter describes breathing meditation that results in a body "like withered wood" and a mind "like dead ashes".

Victor Mair (1994:371) presents Zhuangzi evidence for "close affinities between the Taoist sages and the ancient Indian holy men. Yogic breath control and asanas (postures) were common to both traditions." First, this reference to "breathing from the heels", which is a modern explanation of the sirsasana "supported headstand".

Second, this "bear strides and bird stretches" reference to xian practices of yogic postures and breath exercises.

Mair previously (1991:159) noted the (c. 168 BCE) Mawangdui Silk Texts, famous for two Daodejing manuscripts, include a painted text that illustrates gymnastic exercises–including the "odd expression 'bear strides'."

Xingqi jade inscription[edit]

Some writing on a Warring States era jade artifact could be an earlier record of breath meditation than the Neiye, Daodejing, or Zhuangzi (Harper 1999:881). This rhymed inscription entitled xingqi 行氣 "circulating qi" was inscribed on a dodecagonal block of jade, tentatively identified as a pendant or a knob for a staff. While the dating is uncertain, estimates range from approximately 380 BCE (Guo Moruo) to earlier than 400 BCE (Joseph Needham). In any case, Roth (1997:298) says, "both agree that this is the earliest extant evidence for the practice of guided breathing in China."

The inscription says:

Practicing this series of exhalation and inhalation patterns, one becomes directly aware of the "dynamisms of Heaven and Earth" through ascending and descending breath.Tianji 天機, translated "dynamism of Heaven", also occurs in the Zhuangzi (6, tr. Mair 1994:52), as "natural reserves" in "Those whose desires are deep-seated will have shallow natural reserves." Roth (1997:298-299) notes the final line's contrasting verbs, xun 訓 "follow; accord with" and ni 逆 "oppose; resist", were similarly used in the (168 BCE)Huangdi Sijing Yin-yang silk manuscripts.

Han Dynasty[edit]

As Daoism was flourishing during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), meditation practitioners continued early techniques and developed new ones.

Huainanzi[edit]

The (139 BCE) Huainanzi, which is an eclectic compilation attributed to Liu An, frequently describes meditation, especially as a means for rulers to achieve effective government.

Internal evidence reveals that the Huainanzi authors were familiar with the Guanzi methods of meditation (Roth 1991:630). The text uses xinshu 心術 "mind techniques" both as a general term for "inner cultivation" meditation practices and as a specific name for the Guanzi chapters (Major et al. 2010:44).

Several Huainanzi passages associate breath control meditation with longevity and immortality (Roth 1991:648). For example, two famous xian "immortals":

Heshang gong commentary[edit]

The (c. 2nd century CE) Daodejing commentary attributed to Heshang gong 河上公 (lit. "Riverbank Elder") provides what Kohn (2008:118) calls the "first evidence for Taoist meditation" and "proposes a concentrative focus on the breath for harmonization with the Dao."

Eduard Erkes says (1945:127-128) the purpose of the Heshang Gong commentary was not only to explicate the Daodejing, but chiefly to enable "the reader to make practical use of the book and in teaching him to use it as a guide to meditation and to a life becoming a Taoist skilled in meditative training."

Two examples from Daodejing 10 (see above) are the Daoist meditation terms xuanlan 玄覽 (lit. "dark/mysterious display") "observe with a tranquil mind" and tianmen 天門 (lit. "gate of heaven") "middle of the forehead". Xuanlan occurs in the line 滌除玄覽 that Mair renders "Cleanse the mirror of mysteries". Erkes (1945:142) translates "By purifying and cleansing one gets the dark look", because the commentary says, "One must purify one's mind and let it become clear. If the mind stays in dark places, the look knows all its doings. Therefore it is called the dark look." Erkes explains xuanlan as "the Taoist term for the position of the eyes during meditation, when they are half-closed and fixed on the point of the nose." Tianmen occurs in the line 天門開闔 "Open and close the gate of heaven". The Heshang commentary (tr. Erkes 1945:143) says, "The gate of heaven is called the purple secret palace of the north-pole. To open and shut means to end and to begin with the five junctures. In the practice of asceticism, the gate of heaven means the nostrils. To open means to breathe hard; to shut means to inhale and exhale."

Taiping jing[edit]

The (c. 1st century BCE to 2nd century CE) Taiping Jing "Scripture of Great Peace" emphasized shouyi "guarding the One" meditation, in which one visualizes different cosmic colors corresponding with different parts of one's body.

Besides "guarding the One" where a meditator is assisted by the god of Heaven, the Taiping jing also mentions "guarding the Two" with help from the god of Earth, "guarding the Three" with help from spirits of the dead, and "guarding the Four" or "Five" in which one is helped by the myriad beings (Kohn 1989b:139).

The Taiping jing shengjun bizhi 太平經聖君祕旨 "Secret Directions of the Holy Lord on the Scripture of Great Peace" is a Tang-period collection of Taiping jing fragments concerning meditation. It provides some detailed information, for instance, interpretations of the colors visualized.

In the year 142, Zhang Daoling founded the Tianshi "Celestial Masters" movement, which was the first organized form of Daoist religion. Zhang and his followers practicedTaiping jing meditation and visualization techniques. After the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice rebellion against the Han Dynasty, Zhang established a theocratic state in 215, which led to the downfall of the Han.

Six Dynasties[edit]

The historical term "Six Dynasties" collectively refers to the Three Kingdoms (220–280 AD), Jin Dynasty (265–420), and Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589). During this period of disunity after the fall of the Han, Chinese Buddhism became popular and new schools of religious Daoism emerged.

Early visualization meditation[edit]

Daoism's "first formal visualization texts appear" in the 3rd century (Kohn 2008a:118).

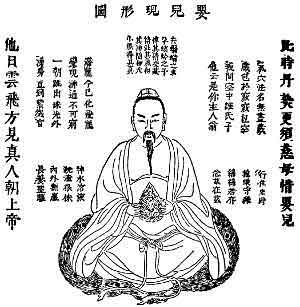

The Huangting jing 黃庭經 "Scripture of the Yellow Court" is probably the earliest text describing inner gods and spirits located in the human body. Meditative practices described in the Huangting jing include visualization of bodily organs and their gods, visualization of the sun and moon, and absorption of neijing 內景"inner light".

The Laozi zhongjing 老子中經 "Central Scripture of Laozi" similarly describes visualizing and activating gods within the body, along with breathing exercises for meditation and longevity techniques. The adept envisions the yellow and red essences of the sun and moon, which activates Laozi and Yunü 玉女 "Jade Woman" within the abdomen, producing the shengtai 聖胎 "sacred embryo".

The Cantong qi "Kinship of the Three", attributed to Wei Boyang (fl. 2nd century), criticizes Daoist methods of meditation on inner deities.

Baopuzi[edit]

The Jin Dynasty scholar Ge Hong's (c. 320) Baopuzi "Master who Embraces Simplicity", which is an invaluable source for early Daoism, describes shouyi "guarding the One" meditation as a source for magical powers from the zhenyi 真一 "True One".

Ge Hong says his teacher Zheng Yin 鄭隱 taught that:

The Baopuzi also compares shouyi meditation with a complex mingjing 明鏡 "bright mirror" multilocation visualization process through which an individual can mystically appear in several places at once.

Shangqing meditation[edit]

The Daoist school of Shangqing "Highest Clarity" traces its origins to Wei Huacun (252-334), who was a Tianshi adept proficient in meditation techniques. Shangqing adopted the Huangting jing as scripture, and the hagiography of Wei Huacun claims a xian "immortal" transmitted it (and thirty other texts) to her in 288. Additional divine texts were supposedly transmitted to Yang Xi 楊羲 from 364 to 370, constituting the Shangqing scriptures.

Lingbao meditation[edit]

Beginning around 400 CE, the Lingbao "Numinous Treasure" School eclectically adopted concepts and practices from Daoism and Buddhism, which had recently been introduced to China. Ge Chaofu, Ge Hong's grandnephew, "released to the world" the Wufu jing 五符經 "Talismans of the Numinous Treasure" and other Lingbao scriptures, and claimed family transmission down from Ge Xuan (164-244), Ge Hong's great uncle (Bokenkamp 2008:664).

The Lingbao School added the Buddhist concept of reincarnation to the Daoist treadition of xian "immortality; longevity", and viewed meditation as a means to unify body and spirit (Robinet 1997:157).

Many Lingbao meditation methods came from native Chinese traditions, such as visualizing inner gods (Taiping jing), and circulating the solar and lunar essences (Huangting jing and Laozi zhongjing). Meditation rituals changed from individuals practicing privately to Lingbao clergy worshipping communally; frequently with the "multidimensional quality" of a priest performing interior visualizations while leading congregants in communal visualization rites (Robinet 1997:167).

Buddhist influences[edit]

During the Southern and Northern Dynasties period, the introduction of traditional Buddhist meditation methods richly influenced Daoist meditation.

The (c. late 5th-century) The Northern Celestial Masters text Xishengjing "Scripture of Western Ascension" recommends cultivating an empty state of consciousness called wuxin無心 (lit. "no mind") "cease all mental activity" (translating Sanskrit acitta from citta चित्त "mind"), and advocates a simple form of guan 觀 "observation" insight meditation (translating vipassanā from vidyā विद्या "knowledge") (Kohn 2008a:119).

Two early Chinese encyclopedias, the (c. 570) Daoist encyclopedia Wushang biyao 無上秘要 "Supreme Secret Essentials" and the (7th century) Buddhistic Daojiao yishu 道教義樞 "Pivotal Meaning of Daoist Teachings" distinguish various levels of guan 觀 "observation" insight meditation, under the influence of the Buddhist Madhyamaka school's Two truths doctrine. The Daojiao yishu, for instance, says.

Tang Dynasty[edit]

Daoism was in competition with Confucianism and Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), and Daoists integrated new meditation theories and techniques from Buddhists.

The 8th century was a "heyday" of Daoist meditation (Kohn 2008a:119); recorded in works such as Sun Simiao's Cunshen lianqi ming 存神煉氣銘 "Inscription on Visualization of Spirit and Refinement of Energy", Sima Chengzhen 司馬承禎's Zuowanglun "Essay on Sitting in Forgetfulness", and Wu Yun 吳筠's Shenxian kexue lun 神仙可學論 "Essay on How One May Become a Divine Immortal through Training". These Daoist classics reflect a variety of meditation practices, including concentration exercises, visualizations of body energies and celestial deities to a state of total absorption in the Dao, and contemplations of the world.

The (9th century) Qingjing Jing "Scripture of Clarity and Quiescence" associates the Tianshi tradition of a divinized Laozi with Daoist guan and Buddhist vipaśyanā methods of insight meditation.

Song Dynasty[edit]

Under the Song Dynasty (960–1279), the Daoist schools of Quanzhen "Complete Authenticity" and Zhengyi "Orthodox Unity" emerged, and Neo-Confucianism became prominent.

Along with the continued integration of meditation methods, two new visualization and concentration practices became popular (Kohn 2008a:119). Neidan "inner alchemy" involved the circulation and refinement of inner energies in a rhythm based on the Yijing. Meditation focused upon starry deities (e.g., the Santai 三台 "Three Steps" stars in Ursa Major) and warrior protectors (e.g., the Xuanwu 玄武 "Dark Warrior; Black Tortoise" Northern Sky spirit).

Later dynasties[edit]

During the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1367), Daoists continued to develop the Song period practices of neidan alchemy and deity visualizations.

Under the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), neidan methods were interchanged between Daoism and Chan Buddhism. Many literati in thescholar-official class practiced Daoist and Buddhist meditations, which exerted a stronger influence on Confucianism (Kohn 2008a:120).

In the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), Daoists wrote the first specialized texts on nüdan 女丹 "inner alchemy for women", and developed new forms of physical meditation, notably Taijiquan—sometimes described as meditation in motion or moving meditation. This Neijia internal martial art is named after the Taijitu symbol, which was a traditional focus in both Daoist and Neo-Confucian meditation.

Modern period[edit]

Daoism and other Chinese religions were suppressed under the Republic of China (1912–1949) and in the People's Republic of Chinafrom 1949 to 1979. Many Daoist temples and monasteries have been reopened in recent years.

Western knowledge of Daoist meditation was stimulated by Richard Wilhelm's (German 1929, English 1962) The Secret of the Golden Flower translation of the (17th century) neidan text Taiyi jinhua zongzhi 太乙金華宗旨.

In the 20th century, the Qigong movement has incorporated and popularized Daoist meditation, and "mainly employs concentrative exercises but also favors the circulation of energy in an inner-alchemical mode" (Kohn 2008a:120). Teachers have created new methods of meditation, such as Wang Xiangzhai's zhan zhuang "standing like a post" in the Yiquan school.

References[edit]

- Bokenkamp, Stephen (2008), "Lingbao," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, ed. by Fabrizio Pregadio, Routledge, 663-667.

- Erkes, Eduard (1945), "Ho-Shang-Kung's Commentary on Lao-tse" Part I, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 8, No. 2/4 (1945), pp. 121-196.

- Graham, Angus C. (1989), Disputers of the Tao, Open Court Press.

- Harper, Donald (1999), "Warring States Natural Philosophy and Occult Thought," in M. Loewe and E. L. Shaughnessy, eds., The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C., Cambridge University Press, 813-884.

- Kohn, Livia, ed. (1989a), Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques, Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies 61.

- Kohn, Livia (1989b) "Guarding the One: Concentrative Meditation in Taoism", in Kohn (1989a), 125-158.

- Kohn, Livia (1989c), "Taoist Insight Meditation: The Tang Practice of Neiguan," in Kohn (1989a), 193-224.

- Kohn, Livia (1993), The Taoist Experience: An Anthology, SUNY Press.

- Kohn, Livia (2008a), "Meditation and visualization," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, ed. by Fabrizio Pregadio, 118-120.

- Kohn, Livia (2008b), "Cun 存 visualization, actualization," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, ed. by Fabrizio Pregadio, 287-289.

- Kohn, Livia (2008c), "Ding 定 concentration," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, ed. by Fabrizio Pregadio, 358-359.

- Kohn, Livia (2008d), "Guan 觀 observation," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, ed. by Fabrizio Pregadio, 452-454.

- Luk, Charles (1964), The Secrets of Chinese Meditation: self-cultivation by mind control as taught in the Ch'an Mahayana and Taoist schools in China, Rider and Co.

- Mair, Victor H., tr. (1994), Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu, Bantam Books.

- Major, John S., Sarah Queen, Andrew Meyer, and Harold Roth (2010), The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China, by Liu An, King of Huainan, Columbia University Press.

- Maspero, Henri (1981), Taoism and Chinese Religion, tr. by Frank A. Kierman Jr., University of Massachusetts Press.

- Peerenboom, Randal P. (1995), Law and Morality in Ancient China: the Silk Manuscripts of Huang-Lao, SUNY Press.

- Robinet, Isabelle (1989c), "Visualization and Ecstatic Flight in Shangqing Taoism," in Kohn (1989a), 159-91

- Robinet, Isabelle (1993), Taoist Meditation: The Mao-shan Tradition of Great Purity, SUNY Press.

- Roth, Harold D. (1991), "Psychology and Self-Cultivation in Early Taoistic Thought," Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 51:2:599-650.

- Roth, Harold D. (1997), "Evidence for Stages of Meditation in Early Taoism," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 60.2: 295-314.

- Roth, Harold D. (1999), Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei-yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism. Columbia University Press.

- Sha, Zhi Gang (2010). Tao II: The Way of Healing, Rejuvenation, Longevity, and Immortality. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Ware, James R. (1966), Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei Pien of Ko Hung, Dover.

Women in Daoism

Daoism encompasses a group of philosophical and religious beliefs that have permeated Chinese culture at every level. Daoism is defined by belief in the Dao 道 (referred to as “Tao” in the older Wade-Giles system) means ‘path’ or ‘way’. Dao refers to the formless, limitless aspect of the universe that underlies all of creation. Daoists study and strive to act in harmony with the rhythm of this cosmic force. The Daoist lifestyle incorporates study of classical Daoist philosophy, ritual practices, meditation, and physical exercises.

The school of Daoism that was first practiced at Wudang Mountain, Zheng Yi Dao (正一道 – Orthodox Unity Daoism) was founded in 142 C.E. during the Eastern Han Dynasty. Many of the original Orthodox Unity Daoist practices grew from shamanistic origins, including writing talismans for protection, and using natural herbs and minerals to create health potions. Orthodox Unity Daoists can chose to live in temples, or offer their services while living among the people. Many Orthodox Unity Daoists practice martial arts or medicine. Hundreds of years after the Orthodox Unity School was founded, during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Daoist religion, Buddhism, and local folk practices began to mix, and the Complete Perfection school of Daoism (Quanzhen Dao) emerged. Complete Perfection Daoism is the major monastic form of Daoism today. Complete Perfection Daoists are traditionally celibate, live exclusively in monasteries, and practice“internal alchemy” which seeks to refine the body through breathing exercises, meditation, and visualization practices. In the West, sometimes Complete Reality Daoists are referred to as Daoist Monks, and Orthodox Unity Daoists are referred to as Daoist Priests, but the differentiation does not exist in the Chinese language. There are many similarities among the schools of Daoism, and all Daoists embrace the three jewels of the Dao: compassion, moderation,and humility.

Daoism is occasionally seen as being made up of Philosophical Daoism (Daojia 道家) based on the texts Dao De Jing and Zhuangzi (道德经, 庄子) and Religious Taoism (Daojiao 道敎), which describes the Orthodox Unity and Complete Perfection schools (and others schools). However, this dichotomy ignores connections between the classical texts and Daoist religious practices, and has been rejected by Daoist scholars and historians around the world. The Dao De Jing and Zhuangzi texts offer incredibly insightful and powerful teachings, however, they too are just a part of a vast Daoist literature. Many people are unaware of the existence of the Daozang (道藏 – the Daoist Canon). The Daoist Canon was originally compiled during the Jin, Tang, and Song Dynasties, but the version surviving today was published during the Ming dynasty. The Ming Daozang includes almost 1500 texts, which discuss Daoist history, philosophy, and practice methods. The painstaking and rewarding work of translating the Daozang into English is slowly opening up a deeper realm of Daoist practice for the rest of the non-Chinese speaking world.

Daoist clergy follow a variety of paths. Some withdraw from the community to live as hermits or in monasteries. Others live in villages or cities. The work of Daoists in the community is directed towards healing and renewal. In some areas (mostly notably Hong Kong and Taiwan) Daoist priests also work to create amulets and talismans, and perform magic spells and exorcisms. Other specialists, such as diviners and mediums, bridge the human and divine worlds. Working as an intermediary between the mortal and spirit world, Daoist adepts use their skills to protect the people from malignant forces. On sacred mountains around China, Daoist priests train and practice their arts, and Daoist temples run by laypeople can be found in villages throughout China.

Daoist clergy follow a variety of paths. Some withdraw from the community to live as hermits or in monasteries. Others live in villages or cities. The work of Daoists in the community is directed towards healing and renewal. In some areas (mostly notably Hong Kong and Taiwan) Daoist priests also work to create amulets and talismans, and perform magic spells and exorcisms. Other specialists, such as diviners and mediums, bridge the human and divine worlds. Working as an intermediary between the mortal and spirit world, Daoist adepts use their skills to protect the people from malignant forces. On sacred mountains around China, Daoist priests train and practice their arts, and Daoist temples run by laypeople can be found in villages throughout China.

The various schools of Daoism also systematize native Chinese health and healing techniques that permeate every aspect of day-to-day life, including meditation and visualization exercises, breathing techniques, sexual practices, and dietary modifications, all of which can be referred to as “yang sheng” (nurturing life). In China, the idea of nurturing life embraces many practices aimed at strengthening the body, mind, and spirit. One of the most important lessons to be learned from self-cultivation is the idea of treating the body before it becomes sick. This corresponds with aspects of modern preventative medicine, such as proper diet and exercise. Each individual person’s body is seen as a small-scale model of the universe, and an inseparable part of the natural world. By purifying the body, it can be brought into harmony with the surrounding natural world, which will lead to a greater level of health. Wudang Daoists dedicate their lives to studying and preserving these valuable arts. It is our hope that students of all cultures and religious can enrich

No comments:

Post a Comment